- Home

- Simone Lia

They Didn't Teach THIS in Worm School! Page 5

They Didn't Teach THIS in Worm School! Read online

Page 5

for a long time. When I was waiting for your

next direction, I must have fallen asleep. I might

have been flying for days, or weeks, or even years.

And now look: this looks very much like the

Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya! I can’t

believe that you knew the way, and that I flew

us here.”

“I can’t believe it, either,” I said to Laurence.

114

I had a feeling inside my body that I’d never

experienced before. It was like a million happy

butterflies were fluttering their wings while

singing a pleasant song. I wasn’t even worried

about how we would get home; I could probably

figure that out while taking an afternoon nap.

It was Laurence’s dream to travel here, and

together, without even trying, we’d actually

done it . . . while dreaming!

“DO YOU SPEAK ENGLISH?” Laurence was

shouting at the giraffe.

The giraffe looked at us with her very big eyes.

“COULD YOU GIVE US A RIDE?” he said

slowly, this time doing a little mime.

The giraffe smiled and lowered her head so

that we could climb on. She circled one of the

tall trees, with Laurence and me balancing on

her head.

Laurence turned to look at me. “This is great,

isn’t it?”

Chapter

Nine

116

It really was. I’d never

even dreamed of traveling,

but now here I was, balancing

on a giraffe’s head in Kenya.

Beyond the trees, behind a

low fence, there were lots of

children with their moms and

dads. They were all pointing and

laughing and having fun.

117

The giraffe lowered her long neck to the

ground, and Laurence and I hopped off.

“THANK YOU VERY MUCH,”

he shouted, doing a bow to show

how grateful he was. “Are you

all right, Marcus?” Laurence

asked. “Your skin . . . it looks a little dry.”

I’d been enjoying myself on the giraffe so much

that I hadn’t noticed that my body was shriveling

in the dry heat of the sun. I tried to answer

Laurence but couldn’t move my mouth to speak.

“We’d better find some

mud for you to cool

off in.” Laurence

picked

me up in

his beak

and flew

over some

bushes and trees.

“There’s a swamp!” he said,

forgetting that I was in his beak

and accidentally plopping me

headfirst into the mud, which was

cold and gloopy like thick dark

chocolate frosting on a birthday

cake. I sank to the bottom, and it

felt totally wonderful.

I heard Laurence call to me with

a muffled voice. “Everything OK

down there?”

“Fine and dandy,” I said,

emerging from the swamp and

feeling like new again.

A big piglike creature watched

me wriggle out of my muddy bath.

119

“Hello, piggy,” I said, trying to be friendly

just in case he thought I was a chocolate-covered

snack.

He snorted in my direction, giving me a shower

that washed away the mud.

“Thanks, piggy,” I said, keeping the

conversation going just in case he now thought

I was some kind of savory snack.

“That’s not a pig, it’s a pygmy hippo,” said

Laurence, who was reading a sign. “I must say,

it’s very organized here in the Maasai Mara with

these informative signs.”

There were signs everywhere. And there were

also neat paths edged with little fences. It did look

quite different from Laurence’s Africa books.

Laurence must have been thinking the same

thing.

“It’s not how I imagined it would be here,” he

said, hopping along a path. “I do like it; it’s very

tidy. In my safari books, there were a lot more open

spaces and dusty plains. It seemed more natural.”

“I said it before, and I’ll say it again, Laurence.

That’s progress for you.”

Laurence nodded. “That must be what it is.”

I remembered that I was great at navigating,

and I had the butterflies-in-my-tummy feeling

again. “LAURENCE,” I said, a little too

enthusiastically.

“Yes?”

“Let’s go and find that Lake Nakuru.

It can’t be far from here.”

Laurence gasped.

122

“We can meet the flamingos,” I said.

His eyes lit up. I wondered whether I needed

to be asleep to find the way, or whether I might

be able to find it just by using my worm instincts.

“Maybe one of these signs will direct us to the

lake,” Laurence said, hopping speedily along the

path. “Ooh, there’s a map here as well,” he called

out. “Can you come and look at it?”

Silly Laurence, he had obviously forgotten

that I don’t need a map to navigate.

“Psst,” said the pygmy hippo. “If you’re

looking for the flamingos, they live in the

middle of the lake on the other side of

the giraffes’ house.”

He lifted his head

to point out the direction to go.

“Thank you very much,” I said. Even though

he’d told me the way, I probably could have

figured it out with my natural worm instincts.

The hippo gave me another spray of water.

123

It didn’t have quite the same impact, but

hopefully he appreciated the gesture.

I rejoined Laurence, who

looked like he was using

all of his bird brain to try

to understand the map.

It lifted me along the path like a water

slide. This water spraying thing

was probably a local

custom. I filled my

cheeks with water from

a puddle and sprayed

him back.

“Come on,” I said. “I’m the navigator.”

I jumped up onto his back without waiting for

him to lower his neck. I missed and slid down the

side of his wing. Laurence picked me up with

his beak and threw me onto my usual seat.

We flew up past the

tall building, over some

lions and a group

of penguins.

In geography

class at worm school,

we learned that

penguins lived in

cold countries.

Why were there

penguins here in

Africa? Maybe they were

on a safari. That was probably it.

125

“Oh, I see,” Laurence answered.

Just then, I could see something

glistening in the distance.

“They’re on vacation,” I said

confidently. “They’re on the same

safari as the penguins.”

“Oh, look, there are k

angaroos over there,”

said Laurence as we flew over a big hill. “I

didn’t expect to see kangaroos here. I thought

they only lived in Australia.”

126

“Laurence! There it is. . . . It’s over there. I

can see it! I can see it! We’ve made it! It’s Lake

Nakuru!”

We landed at the edge of the lake next to some

tall trees. To celebrate this moment, Laurence

was singing a song. I think it was a song; I didn’t

recognize the tune or the words, but he looked

like he was enjoying the strange noises that were

coming from his beak.

I was about to do a happy

dance, when, from the corner of my eye,

I saw a squirrel. It was a familiar-looking

squirrel. It looked just like the one with

the awful teeth who was friends with

the evil mole.

I had a funny feeling in my belly.

“What are you looking at?” Laurence asked.

The squirrel had darted away, and I was

staring at an empty branch.

“Do you remember that squirrel from before?”

“Ooh, yes,” said Laurence, doing a weird body

shake. “That was when we were almost a stew!”

“I think that I just saw her, Laurence.”

“Why would she be here in Africa?” Laurence

asked. “You must have imagined it.”

“Yes,” I said, laughing. I laughed even though

it wasn’t funny.

I looked up at the tree again, to double-

check. No squirrels. It must have been my silly

imagination.

Chapter Ten

I turned back to Laurence. He was staring

straight ahead with his beak open. He looked

like he’d just seen something spectacular, like a

unicorn or a pile of nachos with cheese on top.

“What is it?” I asked, looking to see if there

was a unicorn, or cheesy nachos.

“It’s them! My flamingo family!” he said with

a soft, crackly voice.

132

Laurence was looking at a small group of pink

birds with long, thin legs who were standing on

an island in the middle of the lake. A tear was

rolling down his cheek.

They really were flamingos. We stood in

silence, watching from a distance. We stared at

them for so long that I started to wonder if the

flamingos were actually real. They were bright

pink with unusual beaks and legs that looked

like twigs. Maybe they were made out of plastic

and twigs?

Then one of the flamingos gracefully bent

down, scooped a fish out of the water, and gulped

it down.

“I think they are real,” I said out loud.

Laurence sighed. “This is where I belong. It’s my

true home. I can’t believe that we actually made it

here,” he said, staring ahead.

I couldn’t believe it, either. I looked at Laurence

and then at the flamingos and then at Laurence

again. He still looked like a chicken — a little, fat,

round one. I thought about telling him. Maybe

he hadn’t noticed. But then I remembered about

trying to be kind and that in Laurence’s mind

he was a flamingo. It was probably best to try to

support Laurence in whatever he believed. That’s

probably what a friend would do.

“I’ve always dreamed of meeting other

flamingos, and now it’s finally happening,”

Laurence continued. “I’m one of them.”

“Yes, you are,” I said, lying to Laurence.

“Shall we go and meet them?” Laurence asked.

“Yes,” I said.

134

We flew to the island

in the lake and landed

next to a small group

of flamingos. I couldn’t

help staring at their legs.

Up close they looked

even more like twigs.

Laurence must have

been taking a good look

as well, because one of

the flamingos said to

him, rudely, “What

are you staring at,

little bird?”

“All of you,” he said

boldly, pushing his chest out.

I think he was trying to make himself look a little

taller. “My companion and I,” Laurence said in a

formal voice, “have traveled many, many miles

from a distant land to meet all of you.”

135

He extended his wing to

include me in the conversation.

He sounded and looked a little

like the Queen of England.

O

o

h

!

I cleared my throat and sat up straight,

to appear more regal.

He continued, “All of my life I’ve dreamed of

meeting flamingos and finding true friendship,

happiness, and a sense of belonging. Now that

time has come. As you can probably

tell, I am a flamingo, and it is my

honor to be reunited with all of

you, my brothers and my sisters.”

Laurence’s speech was

actually pretty good.

The flamingos didn’t

say anything at first.

They looked at us

with their beaks

open. I had a

feeling that they

might not be very friendly.

I was right, because then

something horrible happened:

a small flamingo with a scratchy voice started

laughing. It wasn’t the type of nice laughing that

you get when children are running around on a

beach, splashing in the waves. No, it was a cruel,

mocking sound. It made my skin hurt. All of the

other flamingos joined in.

I wanted Laurence and me to be somewhere

else, far away from these horrible birds. I imagined

us being in Paris on a tandem bicycle with two

freshly baked baguettes in the front basket. That

made me happy, being somewhere else.

And then I remembered again that I can’t ride

a bicycle. I felt sad.

Normally in a situation like this, I would have

found an excuse to wriggle away, but because

I was with Laurence and he was standing there

like a bronze statue with its beak wide open

in shock, I had to stand there as well, to try to

be supportive.

The first flamingo lowered his head to

Laurence’s level and whispered, “You’re not one

of us. You’re just a common, plain bird. No one is

interested in your type.”

140

He and his friends turned their backs to us and

walked away on their twigs. I couldn’t believe

how rude he was. I felt really angry. I wanted to

do something that would make a difference. I

powered up my worm brain to think of something

that would help Laurence.

“Should I go and hit him?” I asked.

“No, don’t do that,” Laurence said.

I was glad, because I’d never hit

anyone before. That was another thing

that they didn’t teach us in worm school.

As I stood there

, feeling like a tiny,

helpless worm, I remembered Robert the Bruce.

Well, not Robert, but the spider who inspired him

to never give up. If that spider were here now, he’d

probably tell me to go and stand up for Laurence.

With that in mind, I wriggled over to the

group of flamingos and said in my boldest voice,

“And WHAT do you THINK you are DOING?”

The flamingos turned to look at me.

try

try

try

again

141

They looked confused. “I said, WHAT DO YOU

THINK YOU ARE DOING?”

The flamingos looked at the ground with

sullen faces, suddenly

ashamed. I couldn’t believe

that they were listening

to me! I felt as big as

a tall building.

“We’re not doing

nothing,” mumbled the

one with the scratchy

voice.

“You’re not doing ANYTHING,” I said,

correcting his grammar while wriggling

slowly and deliberately in a circle around the

four of them.

“What’s he doing?” asked a flamingo with

a big beak, who was now looking pretty worried.

“I heard the way that you spoke to this bird,

Laurence.” Laurence flew and stood by my side.

building

me

“YOU flamingos have been very RUDE and

DISRESPECTFUL to him.”

One of the flamingos looked up for a moment,

her face full of indignation.

“I want you to apologize,” I said.

The birds crossed their wings and huffed

and muttered under

their breaths. “I’m

not going to

apologize,” one of

them mumbled.

143

“NOW!” I said, pretending that I was as big as

a skyscraper.

“Sorry, Laurence,” they said in unison.

That was good, I thought. I liked being a

skyscraper. “And WHY are you sorry?”

“For being rude and disrespectful,” they all

said together.

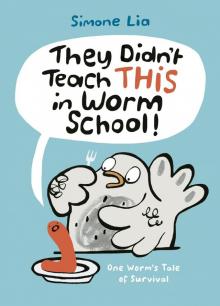

They Didn't Teach THIS in Worm School!

They Didn't Teach THIS in Worm School!